The Power of Owning Your “Bigness”

Throughout history we have been given the message that an acceptable woman is a “small” woman. In response, we’ve been trying to squeeze ourselves into a smaller and smaller forms to appear attractive and palatable to the male cultural gaze.

It’s important to debunk this myth. There’s no payoff for being small.

Throughout time we have been asked to be “small” in so many ways:

- In our physical bodies: wearing corsets, binding our feet, wearing high heels, trying to be physically “slim” and lean at all costs.

- In our personalities: to be quiet, to be polite, to say what people want to hear, to “look the part,” to be tolerant of poor treatment, to carry the burdens of others.

- In our behaviors: to perpetuate the comfortable illusions of others at our own expense, to display the behaviors and traits that don’t threaten the insecurities of those around us.

It is precisely the tension arising from “trying to be other than we are” that creates deep suffering and perpetuates the female “pain body.” Our oppression lies in the splitting within ourselves; the inner rejections, and the ways we’ve let this tension control how we view ourselves.

The oppression of falseness and the hunger for the real

The “myth of smallness” is that if we could only become small enough, then we will finally get the love, approval and support that we deserve. We pour all this energy in meeting impossible standards of appearance and behavior. The truth is that we will never be “small” enough for those that protest our “largeness.” The reason why is because their need for smallness has nothing to do with us personally; It is a projection of the limitations they fear within themselves.

Largeness doesn’t necessarily translate to being more extroverted. It means different things to different people. It simply means being more authentic and allowing the full spectrum of yourself to be revealed, even when it bumps up against cultural norms.

We must refuse to believe the lie that we are most loveable in our attenuated, abbreviated forms.

The danger represented by the “largeness” of the female form is a symbol for something much deeper than our body size or the volume of our voices.

This largeness represents something inherently powerful in us as women…

- our large capacity for expression

- our large capacity to bring change

- our large capacity to be powerful

- our large capacity to love

- our large capacity to heal and transform

- our large capacity to give birth and give death

- our large capacity to feel our emotions and extract wisdom from them

- our large capacity for connection to our bodies and the inner messages

See all external attempts to keep you small for what they really are…

- a fear of your power

- a fear of change

- a fear of the unknown

- a fear of abandonment

- a fear of their own powerlessness

- ignorance of their own possibilities and potential

These fears are not something we need to fight, judge or fix in other people, but simply something to accept as their responsibility to heal while we go on embodying the full truth of who we are. Their ignorance is not our responsibility to fix.

Being your full, unattenuated self is a form of holding space for others to step into their own “bigness” as well.

Many of us grew up watching our mothers wither under the myth of smallness, perhaps teaching us to be small too, in an effort to help us survive. We may have watched our mother’s failed attempts to be seen as valuable and worthy under the myth of smallness. This can be heartbreaking to witness.

Many of us have felt enormous compassion for the ways our mothers’ value was unseen by the larger culture and society. We may have felt that we owe our mothers somehow for their invisibility. This feeling of “owing” is seductive because it feels like it will “put flesh on our mother’s bones” but the tragedy is that it simply cannot. Our mothers have to do their own inner work to become healed and empowered. No matter how much we love other people, the responsibility for their own healing lies within them.

Many of us stayed small because we didn’t want to get approval from the culture that has hurt our mothers so much.

In debunking the “myth of smallness” and breaking the inter-generational enmeshment that inner deprivation fosters, there emerges a new tension; the tension of needing to not over-function for our mothers. There arises the necessary betrayal of refusing to be our mother’s primary source of nourishment. Healing the Mother Wound addresses this “emotional cannibalism” that patriarchy creates between mothers and daughters. We can’t heal them by refusing to own our own lives. This realization opens up the luminous possibility that adult daughters and mothers can become peers, equals or “sisters” on the path of conscious awakening.

We must internally bless our bigness, even when others reject it…

Any woman who desires to be whole and healed may very easily be labeled as “too much” “too intense” or “too big” in this culture. You are probably “too big” for most people. It’s OK. Own it! Not in a defensive, oppositional way, but in simply BEING who you are without apology, without shame and without guilt. Find every opportunity to occupy every cell of who you truly are with joy and love.

There’s nothing wrong with you. You’re not “too big” or “too much.” All those labels were given to us. They never originated with us.

Labels are reflections of the limits of those creating them. Those labels only reflect the limitations of society, not the flaws in human women. They are attempts to control and distract us from the source of our power that lies within us, a source of nourishment that once discovered and owned, makes us unstoppable.

Realizing our complicity in the myth of smallness is essential to vanquishing it

To really give ourselves permission to fully “occupy our largeness” we must be willing to forego the payoffs of our culture that rewards us for being small and non-threatening. Let us praise authenticity wherever we see it, in ourselves and in each other. For example, let’s refrain from praising each other for when we lose weight in an effort to meet the standard of beauty, but instead praise each other when we look happy, healthy, and vibrant. Let’s stop rewarding our silences, our superficial niceties and exhausting standards. Let’s instead praise heartfelt vulnerability, the bold risk to be real, and the courage to risk rejection for the sake of what is true.

As pioneers we must bear the tension of being ourselves in a world that may not be ready to accept us in moments. That’s OK. We can find support in men and women who do “get it” and are actively on the path of living as their real selves.

Our imperfections are interpreted as an assault only by those who haven’t done the necessary inner work to begin to love themselves. Your “imperfections” are expressions of the very things that make you REAL and therefore loveable, reachable, connect-able. Your imperfections are treasures.

You are an abundant, complex, multi-faceted being. Consciously owning this inner abundance is a joy unlike any other. This is wealth.

We all want to be loved for who we really are, not for the mask that the culture says we should wear. The love we receive in exchange for wearing false masks is an empty transaction; a hollow sentiment that never truly nourishes us. It perpetuates the inner deprivation women have been living with for centuries.

We must risk being seen for who we truly are because the love we receive for being real is the only kind of love that truly is truly nourishing.

The more fiercely we love and approve of ourselves, the more we give the message to others that their real self is welcomed and safe to be seen as well. As we do this we can directly recognize the abundance of space there is for ALL of us to flourish!

We realize this by claiming it, not by waiting for others to give it to us. Our fierce claiming of our right to take up space is what creates the space. This space is waiting for each of us to claim it. WE get to decide who and what we are, no one else.

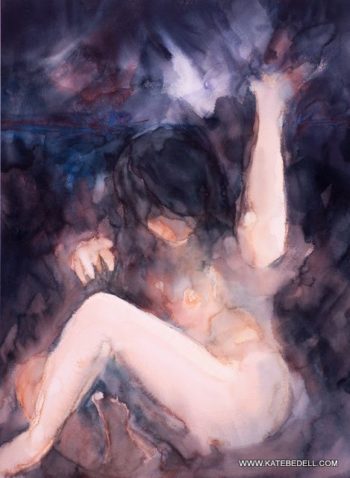

Art credits: “Moving into Light” by Kate Bedell